Agribusiness corporations, including Monsanto, Dow and Syngenta, promised dairy farmers that GMO corn would allow them to reduce the amount of chemicals needed for ample crop production.

But that promise has proved hollow, according to Regeneration Vermont, a pro-organic advocacy group. The nonprofit organization has released a report showing that herbicide and chemical fertilizer use on Vermont dairy farms nearly doubled from 2002 to 2012.

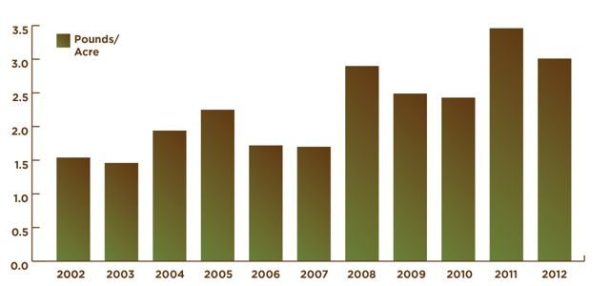

One of the founders of Regeneration Vermont, Will Allen, has graphed data on herbicide and nitrogen fertilizer use from the Vermont Agency of Agriculture. Farmers used 1.54 pounds of herbicide per acre in 2002; that number increased to 3.01 pounds per acre in 2012.

Genetically engineered crops have reduced insecticide use, and are supposed to also lower herbicide use, according to Monsanto literature. Several types of GMO corn can survive exposure to RoundUp, or glyphosate, a powerful weed killer that dissipates quickly in the environment compared with herbicides, such as atrazine, that persist for longer periods of time in the environment.

But the most common herbicides in use are products like Lumax, manufactured by the Swiss company Syngenta, which contain persistent, active ingredients like atrazine and metolachlor. Between 70 percent and 80 percent of herbicides farmers use are some combination of atrazine, metolachlor and a handful of other chemicals, according to state officials.

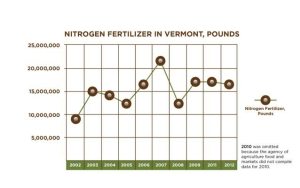

In his 24-page report “Vermont’s GMO Legacy: Pesticides, Polluted Water & Climate Destruction,” Allen found that dairy farmers were using 16.5 million pounds of nitrogen fertilizer on 92,000 acres of farmland as of 2012. A decade earlier, dairy businesses applied half as much, or about 8.9 million pounds of chemical nutrients on about the same amount of acreage, according to data from the Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets.

Eight of the active ingredients in use — atrazine, simazine, acetachlor, alachlor, metolachlor, pendimethalin and glyphsate — have been linked to birth defects, developmental defects and contaminated drinking water, Allen says. Five of the chemicals have been banned by the European Union.

In 2001, scientists like Ray Bressan, of Purdue University, said genetically engineered crops would revolutionize agriculture. “We’ll soon be able to produce more crops with less pesticides, less fuel, less fertilizer, fewer trips over the field. We’ll produce more with less,” Bressan said. “Everyone agrees that agriculture is degrading the environment, but biotechnology has the potential to reverse that.”

Vermont farmers bought that line, Allen says. About 8 percent of corn grown for dairy cow feed was genetically engineered in 2002. Today that number is 96 percent, according to state data. “Vermont fell for it, following national trends and rushing into GMO production,” he writes. GMO corn is by far the state’s biggest crop, Allen says, and it’s a primary source of chemicals contributing to the pollution of Lake Champlain.

Allen, the author of a book on the history of toxic pesticides, “The War on Bugs,” says the promises made by proponents of genetic engineering have not materialized. GMO corn seed and the chemicals used to grow the main crop for dairy cows are expensive, he says, and Vermont farmers are using more pesticides and more fertilizer than ever.

GMO corn, he says, is genetically engineered to repel bugs, including the corn borer and a root worm. The borer affects corn seed, Allen says, but because Vermont farmers use the whole plant for silage, it’s not an issue. The corn worm, in his opinion, also isn’t a major problem for Vermont farmers.

Allen, who founded the Sustainable Cotton Project and runs Cedar Circle Farm, a retail organic vegetable business in East Thetford, argues that more conventional dairy farmers should transition to organic methods that rely on rotational grazing instead of corn silage. Vermont has about 200 organic dairy farms out of a total of 970. Larger farms with 200 or more cows are more likely to use conventional farming methods and confine herds in large barns.

“There is no reason to use GMO corn,” Allen said. The increase in herbicide use, he says, coupled with genetically engineered seeds treated with pesticides “that are not even used to control pests, is irresponsible.”

Cary Giguere, chief of the Agriculture Resource Management Division, the data used in Allen’s report is correct, but the narrative he uses to describe the information from the state agency “represents one perspective, which adds to an anti-conventional agriculture sentiment.”

“He uses a limited selected subset of data to tell a story,” Giguere said by email. “He may have some valid points, however we respectfully feel that it does not capture and present the entire story. The piece is among the many the agency sees advocating that current agricultural practices are somehow not adequately protective. The dataset could also be cherry picked to support the opposing argument.”

Giguere said, however, that most — 70 percent to 80 percent — of the herbicides used are some combination of atrazine, metolachlor and other active ingredients.

Vermont has “very progressive regulations on all environmental fronts and agriculture is not exempt,” Giguere said. The agency’s pesticide program, he said, tracks federal chemical regulations and takes state actions “when we identify that there is a need for additional protections or an unnecessary risk.”

Chuck Ross, the secretary of the Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets, said the state encourages farmers to use less herbicide.

“I think it’s fair to say we’re concerned about chemical exposure and we hope farmers are looking for new ways to skin the cat,” Ross said.

Ross criticized the report for not recognizing farmers’ efforts to lower the use of more-toxic insecticides. Farmers don’t want to use more chemicals than they have to because they are worried about their own health and the environment and weed resistance to herbicides, he said.

“He doesn’t mention there are chemicals that are no longer in use that are more toxic or are a higher exposure risk,” Ross said. “Those subtleties are not mentioned in the report. As an agency, we have moved away from some chemicals and limited others over time.”

Allen says the agency did not make insecticide data available. He asks why, if the state’s programs are so progressive, the agency didn’t join a 2010 lawsuit against Syngenta over atrazine pollution in Midwest water supplies. The suit resulted in a $105 million settlement with water utilities in Illinois and Missouri.

“Why? Because they refuse to enforce any regulations on dairy,” Allen says. “They have not enforced the Clean Water Act for 43 years.”

Ross said it’s “good to have people talk about innovative methods,” but he defended farmers who use GMO corn because it offers “the best yields on the market.” The agency, he said, is not promoting organic farming over conventional dairy and wants to ensure the different approaches can coexist. “Both types need each other to get better,” he said. “I can’t assign a set of values to one form of farming and not another.”

Ross said it’s unrealistic to ask farmers to switch to organic dairying at a time when they are cutting costs to cope with uncertainty in the market. Representatives of the Vermont Farm Bureau declined to comment on Allen’s proposal.

The dairy industry has fallen on hard times over the past year and a half. Milk prices are down to historic lows of about $14 per 100 pounds of milk, far below the cost of production and low prices are expected to last at least another six months. Dairy represents 70 percent of the state’s agriculture economy.

Most dairy farms that use conventional methods have substantially larger herds. Transitioning to organic is costly and complicated, Ross said. Many farmers who are getting ready to retire — the average age is 60 — are not interested in taking a chance on new methods at the end of their careers, he said.

In Allen’s’ view, the agency has not done enough to promote organic dairy methods, and he argues that there is “voluminous evidence that the cost of organic is less and the environmental benefits are substantial.”

Allen also criticizes what he describes as the state’s hypocritical stance on GMO labeling. While state politicians have defended Vermont’s GMO food labeling law against attacks from hostile members of Congress and litigation pushed by the Grocery Manufacturers of America, they have done little to effect policy that would help dairy farmers shift to organic methods, according to Michael Colby, a longtime activist and one of the co-founders of Regeneration Vermont.

Allen asserts in the report that Vermont’s GMO labeling law “has left a false impression that it ‘solved’ the GMO problem in the state.”

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” Allen writes. “While we are forcing the labeling of Cheetos and Spaghettios, the state turns a blind eye to GMO corn used to feed cows that produce milk for Agri-Mark and Ben & Jerry’s. GMOs are about more than a (consumer’s) right to know. It’s also about the GMO impact on the environment and the monopolization of the food supply.”

Sean Greenwood, public relations director for Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream, said by email that the company “is seeking cost effective options of non-GMO feed to make it viable for Vermont dairy farms” and is “moving farmers towards regenerative farming practices.”

GMO corn produces a reliable yield per acre, according to Doug DiMento, the communications director for Agri-Mark, which manufactures Cabot Cheese made from Vermont milk. “There’s an expense to it, but you gain more in dependable and higher yields,” DiMento said.

Agri-Mark is a cooperative and members run the organization, he said. “We are bottom up as a dairy farmer co-op,” he said. “It’s not like we could tell farmers what to do, farmers are going to tell us what they want.”

About 75 farms in the Agri-Mark co-op are organic, he said, “but organic is not for every farmer.” Going organic has a “huge cost to farmers,” DiMento said, and that cost is passed on to consumers pay a higher price for organic milk products.