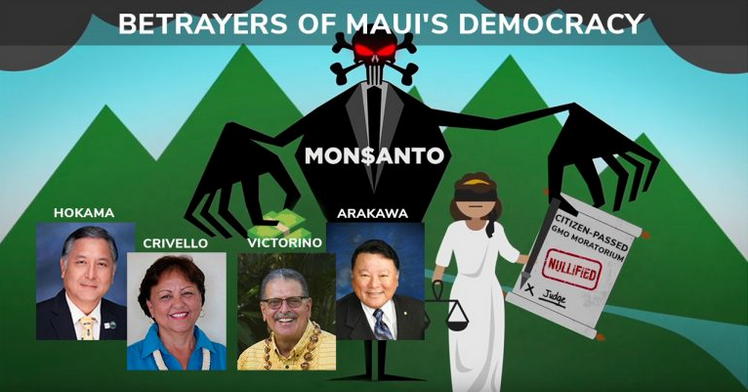

Arakawa, Victorino, Crivello, and Hokama Enabled Monsanto’s Historic Theft of Voter-Approved GMO Moratorium

The public initiative system is a unique and magnificent tool for grassroots democracy.

Four years ago, Maui’s GMO Moratorium made history in a number of significant ways.

First, it made local history by becoming the first public initiative effort in Maui history to get on the ballot. It did this through the hard work of hundreds of volunteers, who surpassed a daunting requirement to get more than 8.465 registered verifiable voter signatures on petitions.

Maui’s 2014 GMO Moratorium also made national history. Monsanto and its agrochemical industry allies spent more money per vote trying to defeat the initiative than any major political contest ever waged in the United States.

Monsanto’s team spent over $8 million, or more than $350 for each of the 22,005 votes that it received. But despite being outspent 80 to 1, Maui’s grassroots initiative won by two percentage points, or 1,000 votes.

The GMO Moratorium banned the pesticide-intensive testing and cultivation of GMO crops until independent testing proved them safe for public health and for Maui’s and Molokai’s island ecosystems. Despite widely advertised propaganda claiming pesticide and GMO safety for humans, independent testing is something that corporate-influenced federal agencies like the Food and Drug Administration and Department of Agriculture have never undertaken.

During the recent trial for Monsanto’s Roundup pesticide, for example, an impartial jury in San Francisco was able to publicly hear the long-suppressed science relating to the toxicity of the weed killer, and weigh this evidence against the most comprehensive scientific safety evidence that Monsanto’s expert legal team could muster. Unlike political appointees managing the F.D.A. and E.P.A. scientific review process of cherry picked corporate results, these jurors were immune to political pressure and inducements for revolving door job payoffs, providing the first truly objective assessment of the impact of pesticides on human health.

After intensive testimony and weeks of evidentiary review, the jury determined that Roundup was indeed the likely cause of a dying groundskeeper’s cancer, and awarded the victim $39 million, while slapping Monsanto with a huge punitive fine for repeatedly lying and hiding critical tests.

The November 4, 2014 passage of the GMO Moratorium initiative was a cause for celebration among public health and clean water advocates locally and around the world. It was achieved through an extraordinary collaboration between parents and residents, allied with Native Hawai’ians, environmentalists, water protectors, and organic farmers. They were concerned that, as Ronnie Cummins, the founder of the Organic Consumers Association observed, “Hawaii is a dumping ground for GMO testing and the dumping of untested chemicals that always accompanies them.”(Most of Monsanto’s GMO testing is done to create seeds engineered to survive the application of massive amounts of a variety of toxic pesticides around them, which, of course, Monsanto also patents and sells).

What happened after the election was even more historic than the passage of Maui’s first public initiative.

Maui County now stands in the textbooks of American history as the only jurisdiction to ever have the results of a legally passed public initiative nullified by federal court order; the only place in the United States to have local democracy stolen by a corporation from under the noses of its voters.

This historic theft of democracy, a maneuver that Ronnie Cummins calls “genetically modified democracy,” was engineered with the cooperation of Maui Mayor Alan Arakawa and rubber stamped by the complicity of Maui’s County Council.

Two of these Council members, Riki Hokama and Stacey Crivello, are now running for reelection, along with Arakawa, who has been term limited out of the mayor’s office and now wants to be elected to the Council. Mike Victorino, a third former Council member complicit in Monsanto’s 2014 theft of democracy, is running to replace Arakawa as Maui’s next mayor

Gary Hooser, who challenged the agrochemical industry while a Council Member in Kauai, felt that judicial nullification of Kauai’s pesticide regulations and Maui’s GMO Moratorium violated Hawai’i’s democracy. “There is no state law and there are no court cases before this that keeps us from passing laws to protect ourselves,” Hooser explained. “The state constitution says that the State and all its political subdivisions, which means counties, shall protect the environment and health and water. So as a Council Member It was my job to look out for the people in my community.”

But democracy was creating an inconvenience for the world’s most notorious agrochemical corporation. Luckily for Monsanto, Maui’s mayor and its “old guard” controlled County Council, were in its corner.

On November 13, just one day after lawyers for the GMO Moratorium requested that a state judge compel the County to enforce the terms of the voter-passed initiative, Monsanto’s attorneys filed an action in federal court to grant an injunction blocking the law from taking effect.

During the next 24 hours, an unusual phone conference, meeting and agreement was hammered out privately in the judicial chambers of federal Judge Barry Kurren. To this day the public has no idea what was said during the negotiations that resulted in an agreement, and judicial order, between Maui County and Monsanto to suspend the democratic will of the people until it could permanently be strangled by a higher federal court.

What is clear was who was not represented in that secret negotiation: The people of Maui. The attorneys representing the popularly passed GMO Moratorium were shut out of the meeting. Instead County Counsel Patrick Wong, who reported to and represented Mayor Arakawa, accepted Monsanto’s terms and its self-serving demand that the judicial venue be moved to federal and not state court.

The product of this secret meeting was instantly made public in the form of a judicial order from Judge Kurren, which stated, “In light of the parties’ agreement, and at the request of the parties, the Court hereby enters an injunction, prohibiting the enactment and enforcement of the Ordinance.”

Judge Kurren’s reasoning, described and upheld by federal judge Susan Mollway in an extension of the injunction a year later, was, in a nutshell, that Monsanto’s right to profit from its operations on Maui trumped the right of its citizens to protect their families’ health and their environment.

The federal court couched this in judicial parlance: that the democratic rights of the people of Maui county were “pre-empted” by the power of the federal government, through its (lobbyist influenced) agencies like the F.D.A., to regulate which products and pesticides could be used in commerce. And that regardless of whether people were dying of cancer or that watersheds were being polluted, as long as these federal regulations were followed, local government, even clearly expressed through a passed voter initiative, had no power whatsoever to intervene or limit the corporations “right” to profit.

In essence, with the support of Maui County’s mayor, attorney and Council, the federal court, in a decision that this reporter has named “The Monsanto Doctrine,” conceded that the federal agencies created by Congress to protect public health could be used as legal shields to protect corporations from laws passed by local government to protect public health.

The mental acrobatics required by the federal court to preempt the will of the people and the constitution of the State of Hawai’i required them to find, as Federal District Judge Susan Mollway wrote in her March 19, 2015 ruling extending the injunction, that Monsanto had proven “that there is a likelihood of irreparable injury and that the injunction is in the public interest.”

Attorneys for the SHAKA Movement, who had petitioned and been granted “intervenor” status to defend the GMO Moratorium (after Arakawa and the County Council refused to do so) argued that in a democratic society, implementing, not invalidating, the initiative would be the only way to serve the public interest. They wrote, “[t]he County will greatly undermine the will of the people if it is not compelled to certify the election results approving a ballot measure and implement the law that the majority of Maui voters approved into law.”

The federal judges rejected this argument. Harm to democracy, they determined, was less important than harming the profits of a $15 billion corporation operating in hundreds of other locations worldwide.

Mollway ruled, “This court also concludes that Plaintiffs are likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction staying enforcement of the Ordinance… to the extent having to stop planting GE crops injures the ability of Monsanto and Agrigenetics to compete in the industry and causes them to lose customers, those are injuries that courts have recognized as intangible harms incapable of being redressed Monetarily.”

Through the lens of the federal judges nullifying the only ballot measure ever passed in Maui County, serving the will of the people, as expressed through the legal process by which all government power vests, was somehow less important to the “public interest” than reducing, even by a fraction of one percent, the profitability of a multi-billion dollar corporate super-citizen.

That federal judges, in this aftermath of the Supreme Court Citizen’s United decision, would make such a ruling is, to many, less outrageous than the fact that the public officials sworn and well paid to enforce Maui’s laws would side with Monsanto and betray its citizens. Instead Maui County, through the office of Arakawa’s General Counsel and through the tacit approval of its County Council, which never breathed a word of protest, joined with Monsanto in agreeing to its demands that the GMO Moratorium not be enacted.

A different judicial outcome in federal court might have resulted had Maui’s elected officials demanded that their constituent’s vote be upheld. Instead it was left to the SHAKA movement and Moratorium advocates to defend democracy as outside “intervenors” of a deal agreed to by the County’s own political representatives.

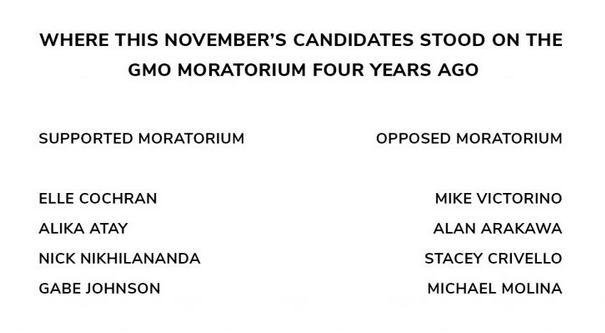

Council Member Alika Atay, who is running for reelection this year a part of the progressive “vote for nine” Maui Ohana slate, was the lead plaintiff in the Monsanto vs. Atay case filed to defend the results of the initiative. In this election, Atay says, “The same people who did not respect our vote are asking us to vote for them again. If you voted yes for the GMO Moratorium and your vote was not respected, come back and vote them out.”

The list of these “same people” who betrayed Maui’s democracy is headed by Alan Arakawa. Having been term limited out of the mayor’s office, Arakawa is now running for County Council in the November 6 election, alongside three other candidates who opposed the GMO Moratorium and then refused to defend the initiative after voters passed it. Riki Hokama and Stacey Crivello are running for reelection to the County Council, while Mike Victorino is running to take Arakawa’s place as Maui’s Monsanto-boosting mayor.

At a meeting with the Chamber of Commerce last month, Victorino indicated that he would continue Arakawa’s defense of pesticide-reliant agrochemical agriculture on Maui, noting that the former sugar plantation lands should be used for food as well as “biocrops.”

Back in October 2014 at a council candidate debate, Victorino said that he opposed the GMO Moratorium because of the loss of jobs that might result. At that time Riki Hokama argued that, “although he supports those that want to decide what to eat, he does not support them imposing their beliefs on him,” as though the GMO Moratorium was about dictating menu choices and not protecting public health and the environment.

Robert Carroll, who is supporting his daughter Claire’s election to fill his seat in the Council, opposed the Moratorium despite its widespread support among his constituents in East Maui. Carroll said the issue had become more “emotional than scientific” and that there was “no hard evidence” to support the initiative.

Mike White, now Chair of the County Council and the lead hatchet man involved in curtailing Council Member Alika Atay’s ability to reform Maui’s plantation era agricultural and water use policies (as reported here) , would not say whether he supported the Moratorium during the 2014 debate. What he did say back then was that, “Once a decision is made, we have a responsibility to carry out the law, whichever way that goes.” What he did, after saying this and getting elected, was to immediately abandon that responsibility, and side with Mayor Arakawa by refusing to oppose the unsavory deal to torpedo the passed initiative.

Mike Molina (currently running for Council against Trinette Furtado), who lost the Council race in 2014 and then joined Mayor Arakawa as his Executive Assistant, called the Moratorium “divisive” and opposed it.

Stacy Crivello went even further in attacking the initiative, arguing that it would somehow harm the “very fabric of my culture,” which she said is “ʻohana.”

During the 2014 race, the leading Council candidate to support the GMO Moratorium was Elle Cochran.

Cochran, who is now running against Victorino in a tight contest for mayor, believes that voters today should pay attention to what happened a few years ago. “The nullification of the GMO moratorium,” Cochran says, “was disappointing on so many levels. The worst thing our government could have done was to overturn the expressed wishes of voters. The voice of the people had been expressed loudly, and then even more loudly, ignored. The implications of carelessly tossing aside a landmark vote like that are damaging to an already fragile voter-base with a historically low voter turn-out rate.”

Mayor Arakawa’s Administration, Cochran observes, “had a duty to represent the people that placed them in office to do just that. But from the beginning it was clear that the Mayor and Corporation Counsel had aligned themselves with Monsanto in the suit, over the will of the people. That is wrong on so many levels. The actions of the administration sent a definitive message to the courts about where county leadership stood on the matter, and that clearly was not with the people.”

Cochran sees the complicity of old guard establishment candidates like Arakawa and Victorino in nullifying the GMO Moratorium as an important reason to elect Maui Ohana candidates like herself.

“As elected officials,” she says, “our primary job is to represent the wishes of our population. We are public servants first and foremost. When elected officials forget that, they can be dangerous to democracy. Legislative decisions become reflective of campaign contributions and lobbyist vested interests, over the will of the people. Voters are our bosses, and get to decide who deserves to sit in these really important seats and speak on their behalf. There are amazing candidates that have sworn to uphold the voice of the people, and there are candidates that already have proven track records that they swore they would uphold that voice, and failed miserably. Choosing your representative wisely this election is paramount.”

Council Member Alika Atay believes that Arakawa and his Council allies abandoned their duty to protect public health as well as local democracy when they sided with Monsanto. “In the 2014 GMO Moratorium vote,” Atay explains, “We said ‘Nuff already with the chemical cocktailing! Now, after the jury verdict in San Francisco, we see that everything we were saying about the harmful effects of Roundup, that it was bad for our families and the next generation, is the truth. The scientific papers that have come out through the trial verify everything that our Maui Miracle vote in 2014 stood for.”

Gabe Johnson, a Moratorium initiative supporter now running for County Council against Riki Hokama (whose major campaign donors, as reported here in the Maui Independent, were mostly from corporate donors with major county contracts) thinks this issue will loom large in this election.

“For those who opposed and overturned the GMO Moratorium, a reckoning is coming,” Gabe Johnson predicts. “People still remember the hours of testimony, the handing out of fliers, the parades, the grassroots efforts. And they remember their vote! So when voters go to the polls this year I think the people who opposed it will be served notice.”

Read full post at http://mauiindependent.org