The consequences of a labeling law in Vermont were not what either side expected.

In 2014, Vermont became the first state to pass a law requiring labels for food that contains GMOs, or genetically modified organisms. GMO-labeling initiatives were soon popping up on ballots all over the country, and Congress eventually passed a national labeling law in 2016.

In the heat of political battle, both sides presented the labeling situation as do-or-die. The Organic Consumers Association, which supported labeling, likened mandatory GMO labels to a “kiss of death” and credited them for driving GMOs out of grocery stores in Europe. On the other hand, opponents of labels argued that they would unnecessarily scare shoppers, as GMOs pose no unique threat to safety despite the negative public perception of them. A GMO label, National Geographic wrote in 2016, might as well be “a skull-and-crossbones.” Tens of millions of dollars were spent in the fights, most of by food companies opposed to labeling.

As Vermont’s law went into effect in July 2016, labeled packages of cereal, candy, salad dressing, bread, and other processed foods—ingredients from GM corn, soybeans, sugar beets, and canola really are ubiquitous on the U.S. food system—appeared on grocery shelves. Two years later, those packages are all still available in American grocery stores, selling as well as ever. The end of GMOs has not come.

A new study has found that Vermont’s GMO labeling law may have even decreased opposition to GMOs. “A lot of policy is made on speculation and assertion,” says Jane Kolodinsky, an author of the study and an economist at the University of Vermont. Because Vermont passed the first GMO-labeling law, it became a sort of natural experiment.

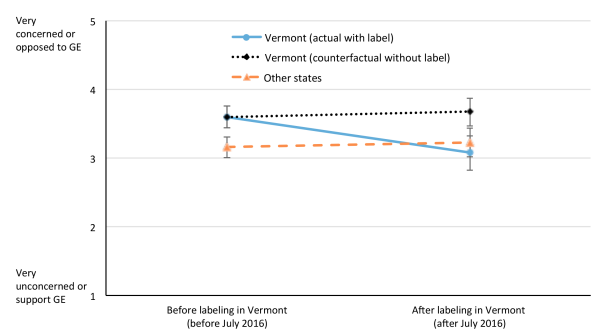

For years, Kolodinsky has conducted a regular poll on consumer attitudes in Vermont that asked, among other things, “Overall, do you strongly support, somewhat support, have no opinion, somewhat oppose, or strongly oppose the use of GMOs in the food supply?” Her coauthor, Jayson Lusk, has also conducted a monthly national Food Demand Survey that included the question, “How concerned are you that the following pose a health hazard in the food that you eat in the next two weeks?” So the two decided to put their data sets together and look at how responses changed before and after Vermont’s labeling law went into effect. The questions from the two surveys were slightly different, but Kolodinsky and Lusk were primarily interested in how attitudes changed over time. And in Vermont, they did change.

JANE KOLODINSKY AND JAYSON LUSK / SCIENTIFIC ADVANCES

“I was surprised,” says Jill McCluskey, an economist at the Washington State University, who was not involved in the study. “Going into it, I thought labels would be viewed as a warning.” Rather, says Kolodinsky, the disclosures may have boosted consumer confidence. If food companies are transparent about using GMOs, then it doesn’t look like they have something to hide.

Gary Marchant, the director of Arizona State University’s Center for Law, Science, and Innovation, says it may not have been the labels themselves that accounted for the change in Vermonter’s attitudes. After all, many national food companies started labeling all of their packages when Vermont’s law went into effect. (It doesn’t make much sense to print a different box just for Vermont.) Yet there was no national shift in concern about GMOs. Perhaps, says Marchant, the local media attention to Vermont’s law and the food industry’s opposition to it made it appear as if the industry wanted to hide its use of GMOs and fed the initial negative perception found in the study. Then the labels appeared, and things calmed down.

Whatever the case, the labels did not radically turn public opinion against GMOs in Vermont. “There was an overreaction by the industry,” says Marchant. “It’s sort of an issue blown out of proportion. In the end, people don’t really care that much.” Anti-GMO activists may not get the reaction want they wanted either.

When Campbell Soup Company did market research about GMO labels before 2016, it found a similarly muted reaction among customers. “They told us they felt better knowing more about our products. Not all of [the customers], but most of them,” says Dave Stangis, the company’s chief sustainability officer. In 2016, Campbell became the first major food company to voluntarily label GMOs in its products. It also broke with the industry association, the Grocery Manufacturers Association, to push for a mandatory national labeling law. Campbell sensed it had more to gain by being open about GMOs. “You shouldn’t be against the consumers’ right to know what’s in their food,” says Stangis.

A few of the proposed USDA labels (USDA)

The nationwide GMO-labeling law passed in 2016 preempts Vermont’s, and it is still in the process of being implemented. The Grocery Manufacturers Association supports the final version of the law now, though critics have argued the requirements are watered down. Instead of using the words “GMO” or “genetic engineering,” the U.S. Department of Agriculture has proposed several label options with the less familiar “BE” or “bioengineered.” Packages could also just have QR codes that consumers then scan for more information. The labeling scheme—which is open for public comment until July 3—is obviously designed to tiptoe around the words “genetic engineering” and “GMO.” But the Vermont study suggests there is no need to be so cagey at all.

read the article here www.theatlantic.com