Last week, Monsanto CEO Hugh Grant sat down with Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson for a wide-ranging, two-part interview about everything Monsanto, from genetically modified crops and the future of agriculture, to the company’s recent spate of PCB lawsuits.

Both sections of the interview are definitely worth the listen for anyone interested in what the agrotech chief has to say about Monsanto’s ongoing string of controversies—or as Hobson puts it—how “Monsanto has become the face of corporate evil in this country.”

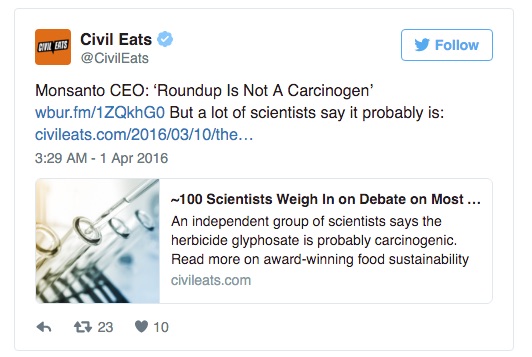

One of the most interesting takeaways was Grant’s insistence on the safety of glyphosate, the world’s most popular herbicide and the main ingredient in the Monsanto’s flagship product, Roundup.

Last year, the controversial chemical was infamously declared a possible carcinogen by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a point that Monsanto has vehemently denied and has demanded a retraction.

Here’s what Grant had to say to Hobson’s question on this issue:

Hobson: People think your Roundup pesticide could be linked with cancer and other health problems. How do you respond to that?

Grant: Roundup is not a carcinogen. It’s 40 years old, it’s been studied; virtually every year of its life it’s been under a review somewhere in the world by regulatory authorities. So Canada and Europe just finished. Europe finished their review last year and came back with glowing colors. The Canadians were the same and now we are going through a similar process in the U.S., so I’ve absolutely no concerns about the safety of the product.

As Grant said in the interview, both Health Canada and the European Food Safety Authority(EFSA) have rejected the IARC’s findings. However, just last month, 94 scientists from around the world came out in defense of the IARC’s original findings, as Dr. Doug Gurian-Sherman pointed out on Civil Eats.

The scientists published their findings in an article for the peer-reviewed Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. The paper argues that the authors of the EFSA’s Renewal Assessment Report (RAR) dismissed incidences of glyphosate-induced cancer in lab animals as chance occurrences and also ignored important laboratory and human mechanistic evidence of genotoxicity. They also argue that the EFSA’s Renewal Assessment Report overly relied on “non-publicly available industry-provided studies” to come up with its conclusion.

Gurian-Sherman, who is the Center for Food Safety’s director of sustainable agriculture and senior scientist, wrote on Civil Eats:

“The article makes a complex but compelling argument in IARC’s defense. For example, the authors explain how EFSA unfairly discounted several good long-running epidemiology studies that showed higher-than-average levels of non-hodgkin’s lymphoma in farmers or farmworkers. They also argue that EFSA did not adequately account for the long latency period before cancer develops. In other words, lack of cancer in some studies is not compelling because they may have not been conducted for a long enough period of time.”

He also noted that “the most dramatic increases in glyphosate use have occurred only in the past five to 10 years—not long enough for most cancers to develop.”

In fact, according to the most recent government estimates, glyphosate use in the U.S. is at nearly 300 million pounds for 2013, up from 20 million pounds in 1992.

The authors of the paper concluded:

“Owing to the potential public health impact of glyphosate, which is an extensively used pesticide, it is essential that all scientific evidence relating to its possible carcinogenicity is publicly accessible and reviewed transparently in accordance with established scientific criteria.”

The conflicting conclusions of the IARC and the EFSA have especially raised concerns about the use of glyphosate in parts of Europe. Government officials in France, The Netherlands, Sweden and Italy are pushing firmly against the herbicide’s relicensing in the European Union over health and safety risks.

Washington appears to be responding to calls from advocacy groups and farmers to study the environmental and human health impact of rampant pesticide use.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency internal watchdog group, the Office of Inspector General, announced late last month that it is opening an investigation into “herbicide resistance,” or the spread of superweeds, as well as the human health impacts of chemicals that are used to fight superweeds.