The Man With the Plan: Mahi Pono’s new general manager Larry Nixon wants more bees and bugs and less corporate hierarchy as he rehabilitates and replants Central Maui’s cropland

FEBRUARY 27, 2019 BY DEBORAH CAULFIELD RYBAK

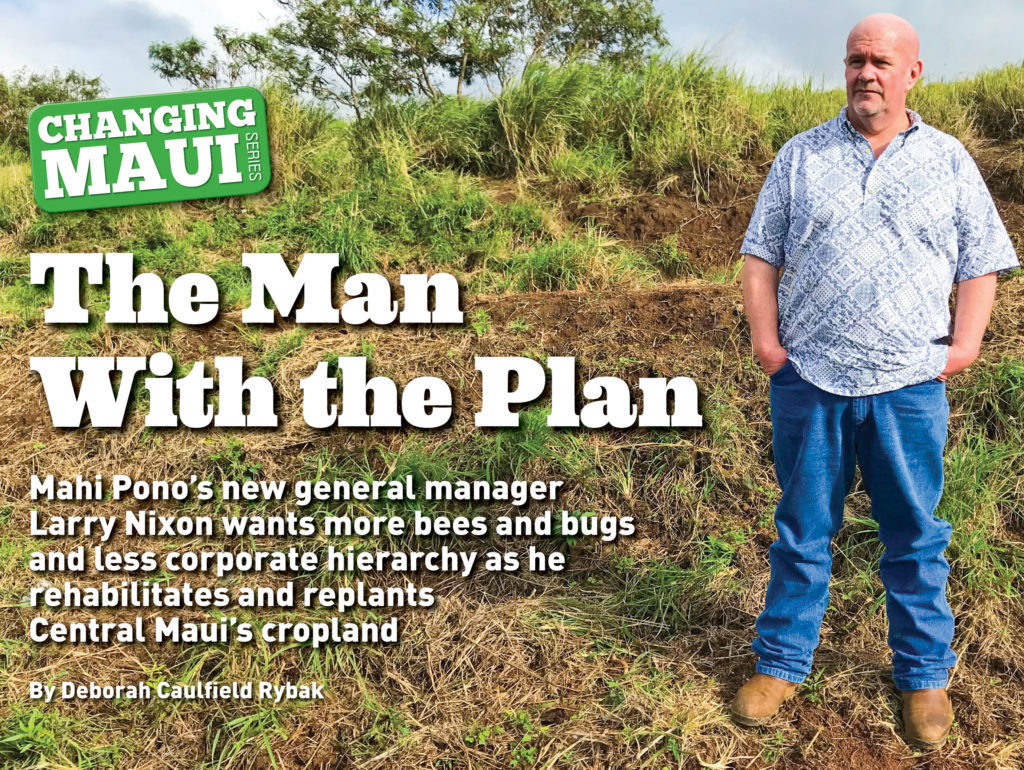

Larry Nixon stands in the middle of a storm-muddied dirt road off Haleakala Highway near Pukalani, his sturdy Justin boots planted firmly on the ranch block known as “the 300s,” some of the finest growing soil to be found on Maui. “Imagine this,” he says, gesturing toward the frenzied expanse of wild sugarcane rushing down to the distant Hana Highway. “Imagine permanent crops in straight rows, solid green, using only the water needed, as far as you can see. It’s beautiful.”

At first glance, Nixon – big, bald, and burly – seems the last person to wax poetic about, well, anything. But this formidable physical presence is quickly mitigated by his nonstop wisecracks and kind blue eyes. Those eyes, however, miss nothing – particularly when it comes to agriculture.

Born and raised in Bakersfield, California, Nixon, 48, began his career working for two of the largest and most successful growers in the state. Ever had a Cutie mandarin orange? Nixon ran that unit for Sun Pacific when the product launched. Today, Cuties are second only to Chiquita in produce name recognition. More recently, he spent four years on the Big Island growing macadamia trees out of lava rock for MacFarm. After only a month at Mahi Pono, Nixon is putting the final touches on the highly anticipated crop plan and assembling the crew and equipment necessary to make it happen. I agreed not to ask Nixon about plan specifics if he would talk about his farming philosophy and how it will manifest here on Maui. Here are excerpts from that conversation.

Deborah Caulfield Rybak: When you first saw the land, what was your reaction?

Larry Nixon: I was disappointed. [Alexander & Baldwin] were good sugar people, but I don’t think they were the best farmers in the world. I expected the farm ground to be better cared for – it’s where your food comes from. It’s just messy. Look at this [points to pipe debris lying by the side of the road]. This is litter. That [indicates debris pushed against a nearby water ditch], that’s just laziness.

DCR: So if this land were a house–

LN: It’d be the one that nobody wanted to visit in the neighborhood. If somebody had broken-down cars or broken sprinkler pipes in their yard, would you want to stop there?

DCR: And what about the condition of the soil?

LN: The soil’s unhealthy, but I don’t think there’s anything bad in there – you can tell sick ground because stuff doesn’t grow back – but right now it’s not ready for new trees. We need to get it healthy. People keep saying, “Oh, we don’t know what’s on this ground. We don’t know what A&B did. We’ll never know.” Yeah, you will. We’re taking 1,100 soil samples the right way – with a backhoe. And when we get the results, we’ll share them.

DCR: I see a lot of plastic in the soil. What are you going to do?

LN: I’m going to get it out. I know there’s stuff that can break it down, but everything that breaks down leaves something behind. I don’t have the time to wait for it to break down. I would rather come in and sift it, get it off island and not contend with it.

DCR: Wow. Where did this environmental philosophy come from?

LN: I don’t consider cleaning this up to be environmental work. It’s stewardship. It’s pride in land.

DCR: OK, but every farmer doesn’t automatically express this type of stewardship, so where did you learn?

LN: If I told you, you probably wouldn’t believe me.

DCR: Try me.

LN: At Sun Pacific and Paramount [his previous employers in California] there’s a pride in ownership. Everything is pristine. Our trucks are always clean. Our equipment is always clean. Our employees are happy and healthy, and they have the best benefits, and they have the best products. The products command the market share, and they command a premium.

And this all goes back to the health of the product, whether it’s nuts or oranges or table grapes. Clean, healthy nuts, clean, healthy grapes or citrus is what everybody strives for – and I’m not saying big ag companies in California weren’t forced to go that way. Clean, healthy food limits what you can do with nutrient and pesticide. I’m sure there are ways around it, but it’s easier to just get it right. Make no mistake, I’ll do anything it takes, within reason, to get a perfect product, but I don’t need to spray to do that.

DCR: No Roundup?

LN: Roundup is a bad idea, no matter where. Even at your house. And not around your food. Look, you can cut the weeds down and buy into a maintenance program, then you don’t need to continue to pour stuff that’s not on this island originally. I want to take that rougher road, because when you’re done, your finished product is the best on the market. Folks who farm with chemicals do so for performance. I don’t. There are ways around it. Are we going to have spray applications? Of course. There are things with permanent crops that people don’t understand, because there have never been permanent crops here. I only worry if I can’t sleep at night. If I’m a good steward, I’ll sleep.

DCR: So what changes will we notice first?

LN: The cane. We gotta get rid of that cane. And it’s the toughest thing – it’s like a weed. It just keeps coming back. We can’t start anything until we get rid of it. I don’t want to be in the cane business.

DCR: Will you harvest it?

LN: I’m not interested. And I won’t burn cane – good humans don’t burn. What we would be interested in is getting rid of it and using it to mulch. So we’ll come in, break all this up, turn the dirt, then start the regrading process. Cleaning this up and getting things to be pristine doesn’t have an effect on the bottom line. But it will have an effect on my workers and me.

“I won’t burn cane – good humans don’t burn,” Nixon said

DCR: What else does the land need?

LN: Bees. There aren’t enough bees to support me on the island. There are not enough bees on this island to support the island. But I don’t want to be in the bee business. We’re inviting beekeepers to put blocks of hives on the property. It will be lucrative for them if they do it right.

DCR: Do we have other insect problems?

LN: We need butterflies, ladybugs. And you can’t just bring in random insects – we have to research. Just because they’re not in Hawai‘i now doesn’t mean they weren’t there 150 year ago, before monocropping. I want to plant more native trees to attract them. When the day comes that you have to scrape bugs off your windshield when you get home, then I’ll be doing my job.

DCR: The water issue is making news right now. Thoughts?

LN: I don’t get involved in water issues. When you’re the biggest player on the block, everybody assumes you’re out for your interests. That’s not the case. A&B had the message, “Well, if it comes across our land, we’ll divert it and use it.” I don’t need it.

We can do better than this, than these open ditches which worked 150 years ago. We need to be better neighbors and get a method for transmission that works. Plus, tree crops have a limit of water. You can get too much. From a farming perspective, there’s enough for all of us.

DCR: I’m sure Mahi Pono had many applicants for this job. Why do you think they hired you?

LN: Hawai‘i is where I want to be. I understand large-scale farming, but I also get working in Hawai‘i. And [pauses] how do I say this without sounding dumb? I am what I am. I’m really frank, and I try and be polite, but I can play across a couple different avenues. To get production people to work with farming people, it takes an oddball like me. That was my key to success at the other jobs, I spoke both farmer and production.

DCR: You have already hired some former Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company (HC&S) workers and said you plan to have about 80 employees by the end of 2019.

LN: March 1 is the date that all those A&B employees become Mahi Pono employees. And on that day, all the plantation terminology, even in our organizational charts and stuff, is gone. Because it goes to the culture. No more use of the word “chief.” No more gender specific terms like “ditchman.” I don’t mean to offend anyone who had that title, but it doesn’t sound right anymore. Nobody is going to call me “Mr. Nixon” or “Sir.” Everything is first name. Hierarchy doesn’t work for a guy like me. So the folks who worked for A&B and East Maui Irrigation, who have always been associated with the plantation, I want to get them into the fold and to understand that the hierarchy system is gone. The managers will have to buy into the same principles that everybody else is buying into.

DCR: You recently met a Brazilian agronomist on island who inspired you to change your farm restoration plan.

LN: He uses a layering effect with native grasses to bring the soil back. They’re taking the worst soil in Brazil and turning it into productive farmland. I would like to showcase his work. We’ll regenerate the soil through native grasses. And we’ll need some revenue generation. I’m not interested in corn and soybeans and all that, but there’s room for some alfalfa and oats and barley.

DCR: Hops for the local breweries?

LN: I’m not into growing sinful crops.

DCR: What?

LN: Oh [chuckles] that’s what I call them. But [Canadian pension fund] PSP says we can’t have hemp or be associated with alcohol-related crops, like wine grapes. Or drug crops like marijuana.

DCR: But hemp’s not a drug.

LN: Well, we’re looking at it, but hemp’s not that great a cash crop. I’m not planning for it, because if I don’t have to do it and it doesn’t benefit Maui, I’m probably not that interested.

DCR: You’ve worked in citrus, in nuts, in pomegranates and potatoes. Do you have a favorite?

LN: I like growing citrus; there’s something cool about it. There’s a connection to it. It hangs there; you can see it. Plus, not everybody can do it. I think the more exotic stuff may become my new favorite. For example, no one has grown commercial liliko‘i in the Pacific in years.

DCR: I know you aren’t ready to discuss the formal crop plan, but can you tell me about your business plan for these yet-to-be-announced crops?

LN: It’s obvious by my appearance – I’m a Krispy Kreme guy. I like Costco’s hot dogs. I don’t eat kale. I don’t drink coffee, so you won’t hear me talking about, oh, we have the best coffee. I don’t know. But I can tell you the citrus, the mac nuts, the avocados will be premium. I want to be the best brand in the Pacific. And I’m not talking about a Mahi Pono brand; I mean a Maui brand. I had to explain that to somebody this morning. This nursery said, “I’ll give you an exclusive on a variety that only you will have.” I said, “Great. I have a grower going into the community farm who wants avocados.” They said, “Oh no, I mean for Mahi Pono.” I said, ‘No, the exclusive is with us, as an island, not Mahi Pono. At some point, when the trees mature, and I have the production facility, we’ll run them through as Maui avocados, not Mahi Pono avocados.”

DCR: Really?

LN: Sure. If I buy varietals only for Mahi Pono, my neighbors can’t benefit. That means I’m encouraging my neighbors to plant what I deem to be a lesser variety of avocado. It goes back to “the big guy took it all.” Everybody needs to understand that if we want something, it’s for Maui, not Mahi Pono. It’s the right way to do it. If we can command top prices for our products, then we can also sell product to schools at middle margins. I want to feed those schoolkids.

DCR: That’s something, coming from an unmarried man with no children.

LN: Hand those kids something they’ll eat; get them excited about clean, healthy food. Right now, the kid who one day will take my job is in the fifth grade on the island. We need to engage him or her about farming now or we’ll never keep them on Maui. It’s not the easiest way to make a living, but it’s an honorable way.

–

Image 2 courtesy Alexander and Baldwin